Irish to the Core Weekly Blog 9 – The Irish Citizens Army

Living and working conditions in Dublin for the common man and woman in the first two decades of the 20th century were deplorable. The industrial revolution had brought them from the destitute farms to the equally destitute cities. Employers, mostly English accepted trade unions for ‘responsible and respectable’ craftsmen but believed them to be a dangerous weapon for the unskilled. After all, they needed readily available cheap labor to keep their economy rolling.

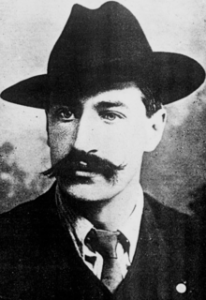

Charismatic James Larkin had been a labor organizer in England and Scotland before he came to Dublin. In 1909 he founded an all-inclusive trade union of skilled and unskilled workers called the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU). He believed that the workers struggle should be waged at the point of production, through sympathetic action, general strikes and if necessary, militancy. This form of unionism was termed syndicalism and mirrored civil unrest movements in many other countries at the time. In fact they fed off each other.

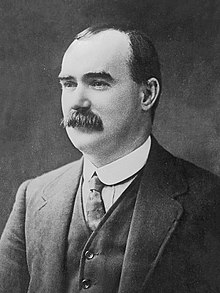

Larkin set up his headquarters named Liberty Hall on the north side of River Liffey just east of Sackville (now O’Connell) Street. It was from there that the Republicans marched at the start of the Easter Rising in 1916. His deputy was James Connolly who would play a pivotal military role in that Rising.

By 1913, the ITGWU was gaining ground. William Murphy, who owned three newspapers and several other businesses chose to gather 400 industrialist sympathizers of his own to oppose this general union. On August 19, These business owners locked out 25,000 workers. Six days later Larkin called a strike against the Dublin United Tramway Company owned by Murphy. On August 31, dubbed Bloody Sunday a militant confrontation killed three workers and injured more than 500. When Larkin was arrested in October, Connolly took over with a call to arms of four battalions of workers militia. When the workers returned to work in January, hungry and defeated, the militia remained, now named the Irish Citizens Army.

During 1914, Larkin returned to lead the ICA. Its military commander was Michael Mallin, who with Countess Markiewicz would command the St. Stephens Green battalion during the Easter Rising. Rifles from the Howth gunrunning replaced previous hurley stick weapons. Sean O’Casey, soon to be a notable playwright was the Secretary of the ICA, believing in orderly civil unrest but not armed conflict. When Larkin left for America in October and Connolly, a staunch socialist Republican took permanent charge, Sean resigned from the group.

Connolly called for insurrection in his newspaper the Worker’s Republic in late 1915 during WWI.

‘An armed organization of the Irish working class is a phenomenon in Ireland. Hitherto the workers of Ireland have fought as parts of armies led by their master, never as a member of any army officered, trained, and inspired by men of their own class. Now, with arms in their hands, they propose to steer their own course, to carve their own future.’

Fearing further unrest, the British allowed the small ICA force of about 200 men and 30 women to drill outside their headquarters.

In early 1916, the Irish Republican Brotherhood conspirators who feared premature military action by the ICA, convinced Connolly to join the IRB’s Military Council to unite forces in preparation for the planned Easter Rising.

The Revolution’s spark was about to ignite.

0 Comments