Questions & Answers

Questions

- What was the Irish Revolution?

- Is there an Irish and a British perspective of the conflict?

- What Irish struggles preceded the Revolution? Who was involved?

- Talk about some of the atrocities and inhumanity levied against the Irish Catholics prior, during and after the revolution.

- Irish from other countries sympathized and supported the conflict. Explain.

- What were the Irish and British political complexities of the revolution?

- Why are the Irish unique?

- Irish myths and legends are full of stories of hidden treasure. Were you influenced by them as you wrote your story and included treasure hunts? How did you integrate this into an already complex story?

- The Irish have historically suffered famine, war, and prejudice. A piece of silver is made more valuable because of the nicks and scrapes called patina. What beautifully unique attributes have centuries of struggle given to the Irish as a people? What makes them unique, strong, powerful? What binds them together?

- How much did the divided religious beliefs of Ireland influence politics, the revolution, independence?

- A great many Irish immigrated to Canada and the US. Why did they leave and why did they choose these countries?

- Many immigrants leave their home countries and by the 3rd generation completely assimilate. Why is the Irish culture so pervasive and pure after generations? It does not seem to matter where they live, the culture remains.

- What compels you to write novels after a career in Aerospace Engineering?

- Why did you select this topic, this revolution, this people as the backdrop for your family saga?

- What surprises did you uncover as you conducted research for your series?

- Who is your reader?

- What do you hope your reader will understand and feel after reading your novels?

- What is the take-away?

- Why eight novels?

- What is your next project?

Answers

Q1: What was the Irish Revolution?

Although there were several important rebellions by the subjugated Irish after finally being conquered by the British at the Battle of Kinsale in 1602, the Irish Revolution to finally break free of British domination took place in the 1915 – 1923 time period. It started with a motivational eulogy in Dublin for the people’s patriot O’Donovan Rossa in August 1915 and was followed by the 1916 Easter Rising of about 1500 Irish Volunteers, mostly academics. This Rising was quickly squashed by overwhelming British forces who destroyed a good portion of downtown Dublin in the process. Armament support from Germany was thwarted at the last minute by British forces. Through this valiant martyrdom and expected harsh British retaliation, the Republicans demonstrated the need for liberty to the country’s citizens.

It took three more years and the end of WWI to mobilize the Irish Volunteers now called the Irish Republican Army (IRA) to break free of Britain. The rebels used the hit-and-run guerrilla tactics that their ancestral Clans had employed so successfully. During this two-year war of independence from 1919 to 1921 the southern, mostly Catholic Republicans formed into flying columns in most of Ireland except the north-eastern mainly Protestant Ulster counties to disrupt police, judicial, and civil British functions. The southern rebels employed a crack Squad of assassins to deplete the British intelligence ranks!

In mid-1921, after Pope Benedict XV pleaded for peace and King George V intervened, Britain proposed a truce to negotiate an Anglo-Irish Treaty which separated Southern Ireland’s 28 counties with a separate commonwealth government that still had to be overseen by the British parliament and who’s citizens still had to swear allegiance to the Crown. Britain would withdraw their military and governmental forces from this large section of Ireland. The remaining 6 counties in Northern Ireland would remain an integral part of Britain.

Britain made it clear that failure to agree would result in devastating consequences for the Irish population.

Michael Collins was a major Republican negotiator of these deliberations and he realized this was the best deal Ireland could get at that point in time. The treaty was signed in London on December 6, 1921 and ratified by the Republican Irish parliament of what became the Provisional government on January 7, 1922.

Eamon de Valera, the President of this New Irish Provisional Government, was dead set against this treaty since it did not liberate the whole island, would result in Catholic Irish citizens continuing to be trapped in Protestant dominated Northern Ireland, and required Irish citizens to swear allegiance to the British monarch.

As a result, a faction of the IRA members and provisional government officials broke away from the pro-treaty forces and became anti-treaty forces. This resulted in a civil war that lasted until May 1923 when De Valera and the anti-treaty forces realized they could not win given the level of British support for their opposition.

Ireland had achieved partial independence but not without a great deal of Irish animosity on both sides which would cause serious problems later in the 20th century.

Q2: Is there an Irish and a British perspective of the conflict?

Of course.

Ireland was colonized by the British in the same manner that Canada, the United States, India, and many other nations were put under British rule during the age of British domination. Britain provided social, political, and economic structure and believed they were a superior civilization. They treated the native citizens as inferior people to be subjugated and used to advance Britain’s interests. In their eyes, the Irish Republicans were unlawful traitors to the Crown to be squashed.

As in the American Revolution, the Irish freedom fighters who had lived under the thumb of harsh British rule, wanted to break free of this oppression, to drive the British out, and to govern themselves. They had centuries of abuse at the hands of the British to fuel their anger and resolve.

The Irish situation was complicated by the religious and economic disparity between the southern counties which were predominantly Catholic and the north-eastern counties which were predominantly Protestant, with Belfast as their economic center. This was caused, in part by a “plantation” of Protestant Scots by Britain during the 17th century.

Q3: What Irish struggles preceded the Revolution? Who was involved?

After the conquest of the Irish Clans by the British at the Battle of Kinsale in 1602 and the subsequent Flight of the Irish Earls to continental Europe in 1607, Britain took control of Irish lands and stamped out the Gaelic civilization. Or so they thought.

Irish freedom fighters revolted on many occasions prior to the revolutionary period 1915 – 1923.

The Confederate Wars 1641 – 1653 took place with Confederate Catholic rebels of Gaelic Irish and old English fighting Protestant English Parliamentarians and Scottish Covenanters who were defying the Catholic King Charles II. Both sides used scorched earth, slash and burn tactics against their opponents starting with a massacre of Protestants in northern Ulster. In the end, a major army of English Parliamentarians who had recently deposed and executed Charles II, and led by the ruthless Oliver Cromwell, brutally suppressed the revolt, and regained control of Ireland.

In the 1688 Catholic King James II was overthrown as king of Great Britain by his Protestant daughter Mary and son-in-law William II from Holland in what was called the Glorious Revolution. James retreated to Catholic Ireland where he hoped to strengthen his army of Jacobites and retake the Kingdom. William landed a force and gained victory over James’s Irish army at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690. The resulting Treaty of Limerick gave some concessions to the suffering Catholic Irish, but later extension of the Penal Laws reversed these civic rights.

In the 1700s many of the English landowners who had confiscated Irish land lived in England and dominated the majority of Irish peasants basically as feudal serfs on what had been their own property. The Anglo-English landowners who lived in Ireland resented the domination of their island by the English and became known as Irish Nationalists. One of their spokesmen in the early 1700s was Jonathan Swift, the political satirist.

Spurred on by the success of the American Revolution against the British, and aided the French, the Nationalists rebelled in 1798 led by Theobald Wolfe Tone. The Dublin rebellion plan was intercepted and British forces quickly squashed the uprising there. There was rebellion in other counties like Wicklow in the south and Antrim in the north. Although the rebels had some early victories, eventually the British forces under John Pratt and Charles Cornwallis won the war.

Two months later, the French under General Humbert provided troops in County Mayo inflicting a major defeat to the British at Castlebar and set up a short-lived Irish Republic with Irish leaders. This lasted only twelve days in September before they were defeated by British forces. Wolfe Tone, himself approached County Donegal by sea in October with a larger French force, but this group of rebels was intercepted at sea and defeated. Wolfe Tone was captured and died in prison through suicide a month later. This rebellion caused Britain to enact the Act of Union in 1801 which consolidated the Irish and British parliaments. At this point only Protestants were allowed to hold office.

Sporadic fighting continued until the rebels were vanquished 1804 after Robert Emmett’s rebellion in 1803. All of these valiant attempts at rebellion were and are lauded by the Republicans who came after them, including the martyr leaders of the 1916 Easter Rising.

In the first half of the 1800s, politician Daniel O’Connell, called the Liberator, emerged as the Catholic champion of the poor Irish men and women. He helped secure Catholic emancipation in 1829 but failed to restore a separate Irish Parliament. In his last years he fought the British as the agrarian crisis of the Great Hunger swept through Ireland. Much later Michael Collins would say that O’Connell was a follower and not a leader of the people.

In the latter half of the 1800s, a radical Protestant landowner, Charles Parnell emerged as the political leader pushing for Irish Home Rule. He wanted Irish self-governance, but as a region within the United Kingdom. The northern Ireland Ulster Unionists and the British Parliament were against Home Rule.

Subsequent to, and as a result of the British oppression during the Great Hunger in the 1840s and 1850s on top of the atrocities that came before, national Fenian patriots such as Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa, John Devoy and James Stephens emerged who founded separatist newspapers and the secret Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) dedicated to political and military overthrow of Britain in Ireland. They issued a proclamation of the Irish Republic and instigated the abortive Republican insurrection of 1867.

Some of these men were incarcerated and treated harshly in prison. Five of these men known as the Cuba 5 were released and exiled from Ireland to America in 1871 where they joined the Clan na Gael. See response to question 5.

From the USA, Rossa personally organized dynamite attacks in London and other British cities in 1881 – 1885. As a result of his efforts and humble upbringing, he was considered the Irish people’s patriot.

Q4: Talk about some of the atrocities and inhumanity levied against the Irish Catholics prior, during and after the revolution.

In addition to the inhumane treatment of the Irish population by the British before the revolution as discussed elsewhere in these Q & As – they were sometimes cited as ‘vermin to be exterminated’. The oppressors continued their punitive methods during the fight for freedom of the 20th century.

The British canons and other weapons destroyed a significant portion of Dublin (their own city) during the Easter Rising 1916. At the end of the one-week rebellion, the British summarily executed the leaders of the Rising without a fair trial and incarcerated thousands of Irish citizens. This helped turn the tide of public opinion against them.

During the guerrilla warfare of the War of Independence 1919-1921 and Civil War 1922-1923, there were atrocities inflicted on both sides which hardened the hearts of the belligerents.

Q5: Irish from other countries sympathized and supported the conflict. Explain.

Irish citizens were left to starve by the British during the Great Hunger, potato famine in the 1840s, 1850s, and 1860s. Those who could afford it traveled mostly to America to survive, with many dying on the way on ‘coffin’ ships. As a result of this and other British atrocities, Irish patriots like O’Donovan Rossa rose up in Ireland with nationalistic intent and were incarcerated by the British. Queen Victoria granted amnesty to some of them in 1871 if they would leave Ireland forever. These patriots including Rossa joined the fledgling Clan na Gael organization when they reached America. This ‘Family of Gaels’ , a brother organization to the secret Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) in Ireland became a driving force, organizationally and financially in the Irish Revolutionary War.

Q6: What were the Irish and British political complexities of the revolution?

That’s a complex question. At the 50,000-foot level, Britain wanted to maintain control of Ireland and its population. They wanted to protect, at the least, their north-eastern Protestant financial base centered in Belfast, at all costs.

The central issue politically was Home Rule for the Irish. By the start of the Great War and after much agitation and debate, the British Parliament under the liberal leadership of Prime Minister Asquith finally passed a third try at a Home Rule Bill called the Government of Ireland Act 1914. This bill would establish a bicameral Irish Parliament in Dublin to deal with most national affairs, but a number of Irish members of parliament would still attend the British parliament. British administration through Dublin Castle would be eliminated, but the British Lord Lieutenant would be retained. This concession was partially like the establishment of a commonwealth nation like Canada had peacefully achieved in 1860.

This Bill was opposed by the House of Lords and Sir Edward Carson and his Ulster Volunteer Force, so Asquith offered to exclude the northern 6 counties temporarily. The upper house still objected, but due to parliamentary procedures they were overruled and the Bill was then given Royal Ascent by King George V.

The southern nationalist Catholic Irish politicians led by John Redmond felt they had achieved a victory, albeit temporarily without the northern counties. Then the World War started and the British Government suspended the implementation of the Home Rule, limited self-government act.

Redmond urged the southern Irish Volunteers to support the war effort with Britain in the hope that this would cement Home Rule when the war ended. Most of the Volunteers signed up to fight on the side of the Allies.

However, after the Easter Rising in 1916, public opinion shifted away from British support toward militant Republicanism and full Irish independence, so Redmond’s party lost its dominance in Irish politics as the Sinn Féin party took control. Redmond died in 1918 and Eamon de Valera, an American by birth emerged as the Republican political leader.

After the prolonged World War at the end of 1918, Ireland, itself was heading into its own War of Independence, insisting on complete independence of the entire country from British control. In the general election, the vast majority of seats were won by the Republican separatist Sinn Féin party. The Government of Ireland Act 1914 was never implemented.

In the midst of the fierce guerrilla Irish War of independence, the British finally passed a fourth Home Rule bill called Government of Ireland Act 1920 which officially partitioned Ireland, North and South.

This further angered the Sinn Féin Republicans to fight on for complete liberation. In July 1921, a ceasefire to the hostilities was established after which the belligerents met in London to negotiate a treaty. Likely realizing that Britain would not agree to total liberation of Ireland, Eamon de Valera sent a delegation led by Michael Collins and Arthur Griffiths to negotiate. As expected, Britain took a hard stand to retain the northern six counties as a part of the UK. The Republican negotiators recognized that reality and agreed to the Anglo-Irish Treaty in December, thereby establishing a provisional Irish Free State for the southern 26 counties. This treaty did, however, necessitate allegiance to the crown by Irish citizens.

This was politically unacceptable to Eamon de Valera, other Sinn Féin leaders and a large fraction of the Irish Volunteers (IRA), resulting in an Irish Civil War where the Irish Free State was supported by Britain. After almost two years of bitter Irish in-fighting that saw Michael Collins assassinated and the anti-treaty forces military leader Liam Lynch killed, and with the Free State National Army gaining strength, Eamon de Valera called a halt to hostilities in May 1923.

The animosities resulting from these wars set the stage for further political and military conflict later in the 20th century.

Q7: Why are the Irish unique?

They believe in Faeries and Leprechauns as do I. See the answer to question 9.

Q8: Irish myths and legends are full of stories of hidden treasure. Were you influenced by them as you wrote your story and included treasure hunts? How did you integrate this into an already complex story?

The story is centered around the clans searching for their family members, loving relationships, freedom for their countrymen and women, and buried family fortunes. These are all linked treasures.

With the exception of the ‘McCarthy Gold’ legend, rather than being influenced by Irish myths about ‘the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow’, I am using historical relics of the Gaelic civilization related to the O’Donnell and McCarthy clans as clues to the riddles of the Clans Pact treasures. I hope that my readers will be left with the question of whether they have been told a tale of fiction or potentially have been on a journey to unearth fascinating buried Irish history.

Beyond this, in Book Eight, Revelation, there are other secular and religious myths and legends that extent beyond Ireland that I have drawn upon for the Clans search for the ultimate prize. And that’s all I’m going to say about that.

Q9: The Irish have historically suffered famine, war, and prejudice. A piece of silver is made more valuable because of the nicks and scrapes called patina. What beautifully unique attributes have centuries of struggle given to the Irish as a people? What makes them unique, strong, powerful? What binds them together?

The long-suffering Irish were tenacious in their fight for freedom. Beaten down, they rose again and again against grim odds. As a result, they became a hard-working race, willing to take on the toughest and most menial jobs with gusto. Remembering their martyrs, they sing their praises, making them a boisterous and outward-going race. The Irish around the world, driven from their homeland , have formed an international bond of brothers and sisters who remember their heritage proudly.

The British built their empire through force and control of the seas. That empire around the world has been overthrown and has now crumbled. The Irish have established a diaspora of countrymen around the world bound together through faith, remembrance and love of their mother country which thrives today in our diverse and challenging world. So who has conquered whom?

Q10: How much did the divided religious beliefs of Ireland influence politics, the revolution, independence?

Religion was the cudgel used by the British to justify conquering the Irish Clans and subjugating the Irish population. The Protestant religion in England resulted from King Henry VIII in the 16th century who broke Britain away from the Catholic faith to avoid excommunication due to divorcing and beheading his wives in search of a son.

The Irish Clans were Catholic resulting from conversion by Irish Saints Patrick, Columba, Adamnan, Brigid, etc. starting in the 5th century. Also the Norman knights who occupied parts of Ireland in the 13th century and who assimilated to become ‘more Irish than the great Clans’, were Catholic. Further, the Catholic Irish in the 16th century allied with Catholic Spanish who were attempting to defeat the British.

After their crushing victory at the Battle of Kinsale in 1602, the British restricted the Catholic Irish population from owning land, voting in elections, holding public office and so forth. After Cromwell’s barbaric squashing of the religiously fueled Confederate Wars uprising in the 1640s, Catholic clergy were expelled from Ireland and liable for instant execution if found. Many of the Irish Catholic churches were demolished.

Although the religious oppression was relaxed in the 17th and 18th centuries, the damage had been done. As a result, after centuries of this brutal religious strife in Ireland, deep-seated animosities between Protestant Britain and the Catholic Irish continue to fester as one major factor in the Irish Revolution in the early 20th century.

The religious strife in Northern Ireland and primarily in Belfast, resulted in the Troubles that were prevalent in the late 20th century between the Catholics and Protestants.

Q11: A great many Irish immigrated to Canada and the US. Why did they leave and why did they choose these countries?

In the 1700s Presbyterian Scots-Irish migrated from Ireland to mainly America to escape religious and economic persecution. America was a land that promised free land and a new start. They were mostly industrious farmers. By the time of the American Revolution in 1775 there were 250,000 in America.

In the 1800s predominantly Catholic Irish citizens immigrated to the United States due to the Great Hunger (Potato Famine) in Ireland. The British overlords took the good foodstuffs and left their Irish servants with rotten potatoes in the 1840s to 1860s. More than a million died of starvation or disease and half a million arrived in America. Those who could afford it were transported in ‘coffin ships’ so named because somewhere between 20 and 50% of the passengers died in transit.

In the 1840s the Irish immigrants comprised nearly half of all the newcomers to the United States.

Q12: Many immigrants leave their home countries and by the 3rd generation completely assimilate. Why is the Irish culture so pervasive and pure after generations? It does not seem to matter where they live, the culture remains.

I think it is the fact that the Irish struggle for freedom was, and to some extent still is hard and extremely painful. This caused the migration of Irish men and women either due to persecution or disease to other parts of the world, mainly the Americas and Australia. Under British domination the Irish had to work extremely hard just to survive. Despite this, millions perished in, for example the Great Hunger of the 19th century.

As immigrants they were willing to take on the hard and often menial jobs with more gusto, being appreciative of their freedom. This caused resentment and resulted in the Irish communities sticking together and remembering their struggles back in the ‘Old Country’ that they missed.

Q13: What compels you to write novels after a career in Aerospace Engineering?

I wanted to continue to utilize my intellect and keep my brain active. My parents were both English teachers and I did well in the subject at the high school level. My English teachers, Mr. Harrison (novels), and Mr. Bull (poetry) challenged me to develop my literary skills. So after 35 years of scientific time-consuming technical projects, my pent-up ideas for creative writing could no longer be contained. I like to think that my parents and grandparents, now gone would look down with grammatical satisfaction on how their nerdy (grand)son has come full circle back to fold of literary prowess, and particularly on the subject of their Irish heritage.

Q14: Why did you select this topic, this revolution, this people as the backdrop for your family saga?

One might assume that with my background I would write science fiction novels about space travel. Maybe someday. My family heritage is Northern Protestant Irish. The Irish struggle for freedom from British rule is in many respects a mirror image of our United States fight for independence some 150 years earlier from the same overlord. So my story, The Irish Clans is a reminder that our democratic freedom is not to be taken for granted and must still be protected from those who would try to destroy it. That topic seems more important to me in today’s socio-political climate. And it relates better to my family story.

Q15: What surprises did you uncover as you conducted research for your series?

Many, regarding the complex heroic struggles for freedom by the Irish patriots individually and collectively, and the interconnections among various relics and artifacts of the Gaelic civilization. That’s what makes this story so fascinating in my opinion.

Q16: Who is your reader?

Anyone interested in Ireland’s struggle for freedom and storied but often mystical history. Anyone who enjoys Dan Brown (da Vinci Code), Catherine Hapka (National Treasure), and/or Diana Gabaldon (Outlander) stories, among others.

Q17: What do you hope your reader will understand and feel after reading your novels?

I hope that through my characters, my readers will have ‘lived’ and better understand the complex and painful struggle for freedom by the Irish people from British domination. Further, I hope that my readers will feel that they have been on exciting hunts for real treasures hidden long ago with historical relics and artifacts as clues to be uncovered. They should wonder whether this is fiction or finally unearthed history.

Q18: What is the take-away?

Freedom from oppression to restore liberty and justice for all is hard-fought and the result, if successful is fragile at best.

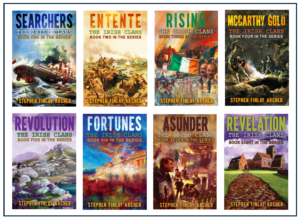

Q19: Why eight novels?

I have a story to tell, a captivating one I believe. Historically it is a complex series of Irish revolutionary events starting with an eulogy in 1915 and ending with a civil war in 1922 – 1923. When I outlined the project I thought it would take four novels to tell. However, as the plotline and fictitious characters evolved, I realized that there were more world events that entered into the conflict, for example World War I, the American entry into it and the connection with Germany. The complexities of the historical Gaelic clues for the treasure hunts and of the protagonists and antagonists searching for them grew as my research unearthed more and more fascinating interconnections.

I have completed writing Book Eight : Revelation and more exciting clues have emerged from the mists of history. This will complete this novel series.

Q20: What is your next project?

I am thinking about a series titled Motherlode about the gold rush in California and perhaps extending to the silver strikes in Nevada, and their impact on development of Western America. There is literary gold and silver to be mined in this exciting part of historical Americana.