The Irish Confederate Wars Part 2 – Irish to the Core Weekly Blog 51

In the last blog I discussed the conflict within England and Scotland during the reign of Charles I from 1625 to 1649. Now let us begin to see how that affected Ireland.

The conflict in Ireland had political, religious and ethnic aspects and was fought over governance, land ownership, religious freedom and religious discrimination. The main issues were whether Irish Catholics or British Protestants held most political power and owned most of the land, and whether Ireland would be a self-governing kingdom under Charles I or subordinate to the parliament in England.

The war in Ireland began with a rebellion in 1641 in the north, Ulster by Irish Catholics. They tried to seize control of the English administration in Ireland. They wanted an end to anti-Catholic discrimination, greater Irish self-governance, and to curtail the plantation of Protestant English Parliamentarians and Scottish Covenanters settlers who were defying King Charles I in Ireland.

The rebellion was intended to be a swift and mainly bloodless seizure of power in Ireland by a small group of conspirators led by Phelim O’Neill. Small bands of the plotters’ kin and dependents were mobilized in Dublin, Wicklow and Ulster, to take strategic buildings like Dublin Castle. Since there were only a small number of English soldiers stationed in Ireland, this had a reasonable chance of succeeding. Had it done so, the remaining English garrisons could well have surrendered, leaving Irish Catholics in a position of strength to negotiate their demands for civil reform, religious toleration, and Irish self-government.

However, the plot was betrayed at the last minute and as a result, the rebellion degenerated into chaotic violence. Following the outbreak of hostilities, the resentment of the native Irish Catholic population against the British Protestant settlers exploded into violence.

Shortly after the outbreak of the rebellion, O’Neill issued the Proclamation of Dungannon which offered justification for the rising. He claimed that he was acting on the orders of Charles I. But Charles condemned the rebellion after it broke out.

These first few months were marked by ethnic cleansing and massacres in Ulster. All sides displayed extreme cruelty in this phase of the war. Around 4,000 Protestants were massacred and a further 12,000 may have died of privation after being driven from their homes. In one notorious incident, the Protestant inhabitants of Portadown were taken captive and then massacred on the bridge in the town.

The settlers responded in kind, as did the Government in Dublin, with attacks on the Irish civilian population. Massacres of Catholic civilians occurred at Rathlin Island and elsewhere. The rebels from Ulster defeated a government force at Julianstown, but failed to take nearby Drogheda and were scattered when they advanced on Dublin.

By early 1642, there were four main concentrations of rebel forces: in Ulster under Phelim O’Neill, in the Pale around Dublin led by Viscount Gormanstown, in the south-east, led by the Butler family – in particular Lord Mountgarret and in the south-west, led by Donagh MacCarthy, Viscount Muskerry.

Next week we will discuss how the rebel forces banded together in the Irish Confederacy.

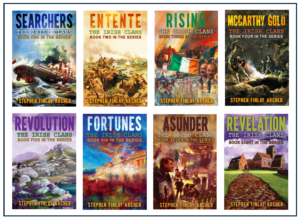

Stephen’s novel series “The Irish Clans” can be purchased at https://amzn.to/3gQNbWi

0 Comments