The Irish Confederate Wars Part 3 – Irish to the Core Weekly Blog 52

This is the one-year anniversary of my weekly blog Irish to the Core. I hope you are finding it helpful and interesting.

In the last blog I discussed that the Confederate Wars in Ireland started in Ulster in 1641, led by Catholic Phelim O’Neill, with great loss of life of Protestants and Catholics alike. O’Neill thought he was supporting King Charles I in England, but surprisingly, the king condemned the rebellion.

The four main concentrations of rebel forces were: in Ulster under Phelim O’Neill, in the Pale around Dublin led by Viscount Gormanstown, in the south-east, led by the Butler family – in particular Lord Mountgarret and in the south-west, led by Donagh MacCarthy, Viscount Muskerry.

The situation in Ireland was even more complex than the evolving road to civil war in England where the Royalist forces of the King were in opposition to the English Parliament and their allies, the Scots.

King Charles I sought to utilize loyal Irish forces, but not the rebels, for his cause in England, but first he had to regain control in Ireland.

Even though they were enemies in terms of the fundamental control of governance for England, Charles and the Parliament had the same overarching objective as far as preservation of conquered land in Ireland. They had signed the last act that they would ever agree to in March 1642 called the Adventurers Act, which funded the war in Ireland by loans that would be repaid by the sale of lands held by the Irish rebels.

During 1642, English Royalist forces retook Dublin. The Parliament, seeing what the king was attempting to do, send 10,000 Scottish troops to Ireland, landing in the north at Coleraine near Derry and Carrikfergus near Belfast.

The four rebel factions mentioned above realized that they would be attacked by two forces likely warring between themselves. So, they banded together in early 1642 to form the Irish Confederacy. They set up their headquarters in Kilkenny Castle seventy-five miles southwest of Dublin. Their strategy was to control the ports of Waterford and Wexford on the southeast coast to maintain a conduit for support from Catholic Europe. By the end of that year, the Confederate rebels (i.e., the previously conquered Irish) controlled two-thirds of Ireland.

Now there were three battling entities in Ireland, the Confederate Catholic rebels, the Royalists supporting the king and the Protestant parliamentarians supported by the Scots.

Most Irish Catholics supported the rebellion, especially Catholic clerics who were being persecuted. Some upper-class Catholics supported the Royalists because they feared losing the land they had been granted during plantation if the Confederates were defeated. Some, like the Burke family of Clanricarde chose to be neutral.

In early 1642, the rebel forces suffered a series of defeats due to inexperienced leadership.

Fortuitously for the rebels, the English Civil War started in August of that year and many of their troops were recalled from Ireland. This allowed Garret Barry, a returned Irish mercenary soldier, to capture Limerick in 1642, while the English garrison in Galway was forced to surrender by the townspeople in 1643.

By mid-1643, the Confederacy controlled large parts of Ireland, the exceptions being Ulster, Dublin, and Cork. Their remaining opponents were also fighting among themselves, with some areas held by forces loyal to Parliament, others by the Royalist Duke of Ormonde and the Covenanters pursuing their own agenda around Carrickfergus. The situation was chaotic with shifting allegiances. Many Ulster Protestants regarded the Scots with hostility, as did some of their nominal allies in Parliament.

The English Civil War gave the Confederates time to create regular, full-time armies and they were eventually able to support some 60,000 men in different areas. These were funded by an extensive system of taxation, equipped with supplies from France, Spain and the Papacy and led by Irish professionals like Thomas Preston and Owen Roe O’Neill, who had served in the Spanish army.

This confusion should have given the Confederates the upper hand to retake Ireland. However, by signing a truce or “Cessation of Arms” with the Royalists on 15 September 1643, then spending the next three years in abortive negotiations, they lost their advantage.

Next week I will discuss the next brutal phase of this rebellion.

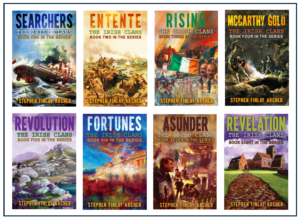

Stephen’s novel series “The Irish Clans” can be purchased at https://amzn.to/3gQNbWi

0 Comments